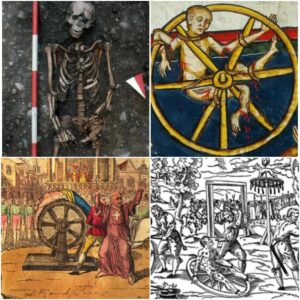

The Catherine Wheel, also known as the breaking wheel, stands as one of history’s most brutal instruments of torture and execution, designed to inflict unimaginable pain and prolong the suffering of its victims. Used primarily in Europe during the medieval and early modern periods, this gruesome device was not only a tool of punishment but also a public spectacle meant to deter crime through fear and horror. Its name, derived from the martyrdom of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, belies the sheer cruelty it embodied, tearing the body apart and ensuring a slow, agonizing death.

Origins and Historical Context

The origins of the Catherine Wheel are murky, but its use became widespread in Europe, particularly in France, Germany, and the Holy Roman Empire, from the Middle Ages through the 18th century. The device was named after Saint Catherine, who, according to legend, was sentenced to death on a spiked wheel in the 4th century, though she was miraculously spared and later beheaded. Ironically, the wheel bearing her name became synonymous with cruelty rather than divine salvation.

The breaking wheel was employed as a punishment for heinous crimes such as murder, robbery, or treason. It was particularly favored in public executions, where crowds gathered to witness the gruesome spectacle. The wheel’s design and method varied by region, but its core purpose remained consistent: to maximize suffering while serving as a stark warning to others.

Design and Mechanism of the Wheel

The Catherine Wheel was a simple yet diabolical device. Typically, it consisted of a large wooden wagon wheel with spokes radiating from a central hub. The victim was tied to the wheel, either spread-eagled on its surface or with limbs threaded through the spokes. The executioner would then use a heavy iron bar, club, or hammer to systematically break the victim’s bones, starting with the limbs.

The process was methodical and deliberate. Each strike shattered bones, leaving the victim’s body mangled but often still alive. In some variations, the wheel was elevated or rotated to intensify the suffering, with the victim’s broken limbs dangling or twisting unnaturally. After the bones were broken, the wheel was sometimes hoisted upright and displayed publicly, leaving the victim to die slowly from shock, blood loss, or exposure over hours or even days.

In certain cases, executioners delivered a “coup de grâce” (a final blow to end the suffering), but this was not always granted, as prolonging the agony was often the point. The wheel’s design ensured that the victim remained conscious for as long as possible, enduring excruciating pain as their body was torn apart.

Archaeological Evidence and Notable Cases

Archaeological discoveries have shed light on the brutal reality of the breaking wheel. In 2019, archaeologists in Poland uncovered the skeletal remains of a man believed to have been executed on the wheel during the 16th or 17th century. The skeleton showed multiple fractures consistent with the method, with bones shattered in a manner that suggested deliberate and repeated blows. Such findings confirm the wheel’s use as a common form of execution in certain regions.

Historical records also document its widespread use. In France, the wheel was a standard punishment for criminals until the 18th century, when more “humane” methods like the guillotine began to replace it. In Germany, the wheel was used in public squares, with executioners sometimes varying the method to suit the crime’s severity. For example, in some cases, the victim’s limbs were woven through the wheel’s spokes before breaking, ensuring even greater torment.

Cultural and Psychological Impact

The Catherine Wheel was more than a physical punishment; it was a psychological weapon. Public executions were theatrical events, designed to instill fear and reinforce social order. The sight of a writhing, screaming victim, their body broken and contorted, left a lasting impression on onlookers. The wheel’s slow, deliberate nature amplified its terror, as victims often lingered in agony for hours, their cries echoing through the crowd.

The device also carried symbolic weight. The wheel, a symbol of motion and progress in other contexts, became an instrument of destruction, turning the body into a grotesque display of suffering. Its association with Saint Catherine added a layer of religious irony, as the tool named for a martyr became a hallmark of human cruelty.

Decline and Legacy

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Catherine Wheel began to fall out of favor as societies moved toward less barbaric forms of punishment. The rise of the guillotine in France, which promised swift and relatively painless executions, marked a shift in attitudes toward public punishment. By the 19th century, the wheel had largely disappeared from European legal systems, though its legacy lingered in historical records and cultural memory.

Today, the Catherine Wheel is remembered as a chilling symbol of medieval cruelty. Its name evokes images of shattered bodies and prolonged suffering, a testament to the lengths to which humanity once went to enforce justice through terror. Archaeological discoveries and historical accounts continue to remind us of its horrors, ensuring that the breaking wheel remains a stark warning of the darkest chapters of human history.

Conclusion

The Catherine Wheel stands as one of the most horrific inventions of the past, a machine designed not just to kill but to destroy the human body and spirit in the most agonizing way possible. Its use in public executions served as both punishment and propaganda, reinforcing societal control through fear. While the wheel has long since vanished from the executioner’s toolkit, its legacy endures as a grim reminder of humanity’s capacity for cruelty and the importance of moving toward justice that prioritizes compassion over vengeance.